In a bitter twist of fate two months ago, all my worst fears came true: COVID19 school closures forced my thriving preschool classroom into a virtual learning environment. It felt a bit ironic considering I wrote a piece last year strongly opposing the online preschool movement in Arizona. When I reread that piece today, I cried some ugly tears. Despite my significant efforts to create a stimulating online environment, my “classroom” is nothing like it used to be. In fact, we are barely hanging on. More than ever before, I am convinced that online environments are not appropriate for young learners. My hope is to share some reflections on this for teachers, parents, therapists, and policy makers. As a parent of a preschooler and a preschool teacher, I’ve learned some things. And I’m sure you have, too. Let’s move forward, smarter together.

As I wrote last year, “Online preschool lacks the authentic learning in real preschool classrooms and disregards the needs of early learners.” This is absolutely true. After a one-week period of rapt engagement with the novelty of Zoom, my students started gradually withdrawing emotionally. I watched their smiles fade, their eyes wander, and their attendance decrease. Some of my students were crying before and after class meetings because they missed their friends. A sadness crept over them that shook me deeply. The students I love started looking like strangers. They weren’t silly. They weren’t playful. Their eyes didn’t sparkle any more. They missed the togetherness so much that I could feel them hurting through the cyber-waves. Without a real classroom environment, they just couldn’t be themselves.

I desperately tried to recover their spirits, but I just couldn’t. I reached out to parents for input and feedback. For some kids, we decided it was too traumatic to continue seeing each other online if we couldn’t be together in person. I told families to allow their kids to lead: If they wanted to come, I would be there. If they weren’t interested or felt sad about class meetings, we would not force any child to participate. For many kids, this has been essential to their happiness. Instead of drawing out our summer goodbye, they needed to move on and adjust to their (very good) lives at home. Working through these individual decisions with families and watching the kids hurt filled me with so much sadness that I wrote about grief last month. I’ve watched my own preschool child struggle with attending Zoom meetings as well. Young kids just don’t understand the idea of virtual togetherness. They crave real connections and experiences.

Many of my students kept asking their parents when they would get to go back to school. In one sweet story, a child asked her mom, “Can I wake up early tomorrow so that I can go to school?” Preschoolers just couldn’t understand why school was closed day, after day, AFTER DAY. That’s because preschool kids live in the time of “now” and that is it. Period. According to Tillman/Barner (2015), children don’t understand the nuances of time until they are SEVEN! Considering I teach 3-5 year olds, many with developmental delays, it’s obvious why their sadness kept snowballing. They couldn’t understand why the “tomorrows” didn’t bring school back. And once they realized that “tomorrow” just brought more virtual learning, they started telling their parents that they weren’t interested.

From this, I have learned two things: First, if a school closure happens again in my preschool teaching career, I would advocate for a one-week “goodbye period” to prepare young kids to stop seeing each other. Then, I would free them to focus on their new days at home while devoting all my time to parent collaboration, co-designing authentic home learning experiences based on each child’s strengths/needs and their parents’ goals for them. Truly, I believe this would have been better for the majority of my students and their families. Seeing each other daily was not the right thing for them emotionally.

Second, I will continue to adamantly oppose any discussion of public funding for online preschool in Arizona. Lawmakers, hear me clearly: My recent experiences strongly affirm the wealth of existing research that screen time increases the chance of depression for youth aged 2-17. In mid-April, my class meeting attendance averaged 12 happy students. This week, my class meetings averaged 6 students ranging from sad to barely happy. And this is shocking because I have been holding a DANCE PARTY this whole week to bring them some smiles. Only half of them dance. The others just watch sadly (but still say they like it). Weird. If you had entered my classroom in February during a dance party, you’d have needed a stun gun to stop them from dancing. Online, their joy is gone. If this year were to keep going, I am sure that I would be the last man standing. Slowly, one-by-one, the kids would have moved on to greener pastures. Arizona preschool kids deserve better opportunities than online learning can offer. And I will keep showing up to fight.

* * * * *

EPILOGUE

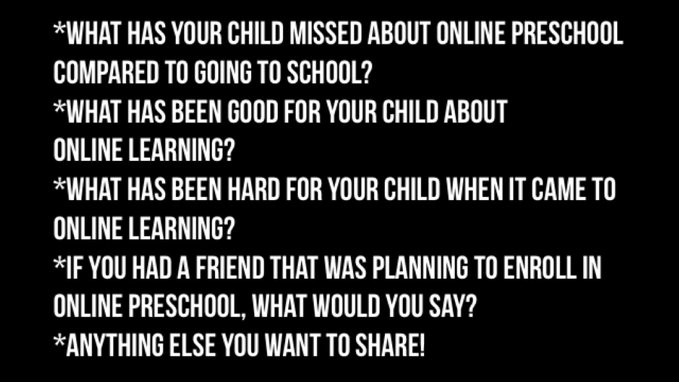

This might be a sad story, but WE get to write the epilogue. What will we learn from this? What worked? What didn’t? If you are the parent or educator of preschool-aged children, consider these questions below and share your experiences in the comments. If you are a policymaker, please read the stories here and the ongoing comments. Let’s make the future better, shall we?

I shared these questions on social media earlier this week, and I have some comments to get this conversation going:

CHALLENGES WITH THE ONLINE PRESCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

In general, parents had a hard time getting their children to attend class meetings or gain benefits from them. Online learning was not engaging for their kids. If school closures return in the fall, what could be done to improve these family outcomes? How can these stories inform decision making about public funding for online preschool? Here are some of their stories:

- “It’s been really hard for him to feel heard, even when he is trying to use his words.”

- “It has been a giant struggle to get my daughter on for class and therapies—I’m talking about a hitting, kicking, and throwing things kind of struggle.”

- “Typical remote online learning and Zoom meetings are ineffective for children who lack basic attending skills which encompasses most significantly impacted children with ASD.”

- “Getting a four-year-old to sit in front of a Zoom meeting requires skills I don’t possess while I’m simultaneously trying to [work].”

- “I feel like the children with [special] needs have been left in the dark.”

- “I couldn’t do the ‘can you go get this’ [when I don’t have something a therapist wants my child to use] every 5 minutes while chasing the little one and trying to keep him in front of the camera.”

- “We tried attending the Zoom meetings, but he’s a mover. It’s too hard to capture what he’s doing on video.”

- “She kicked, screamed, threw everything and wanted nothing to do with it. All her [virtual sessions] got cancelled.”

- “I probably have about 50ish links [from my therapists] that he could care less to watch.”

- “As a parent, I opted out of telehealth services feeling overwhelmed with trying to force my child to attend to the therapist.”

SILVER LININGS AND SUGGESTIONS

Parents and educators invested two months experimenting with virtual learning. The lessons learned are nuggets of wisdom we should cling to. Here are some stories to celebrate or revisit if school closures reoccur:

- “One of his teachers made these amazing bags. She had projects he could do and all the ingredients inside the bag. We picked them up weekly.”

- “We learned that he worked well in the car. It was his calm place.”

- “The positive is that my kids have been able to see their friends and teachers…a sense of normalcy in this crazy world. They look forward to seeing them, but are also confused why we can’t see them.”

- “Sometimes her therapists would try to keep going with an activity even though she was yelling or trying to hit the camera. I could see that she was trying to be finished. So I would just interrupt them and have her say, “Finished” or “One more, then finished.” I found I had to be brave and advocate for her even though I wanted to be respectful, too.”

- “I finally realized I needed to do therapy one place every day in a little corner where I could block her in. This allowed her to stand up and move around freely when she was dancing. It was also helpful for her to have space when she was protesting so that she could yell and stomp around without running away. I gave her the space, only blocking her with my body if she tried to leave completely.”

- “As a teacher, I have found that I have had to really go outside the box to try to pair with my students through silly online videos. By creating educational videos, parents can have their children watch them when convenient and parents are then able to implement some of the activities with their children. It serves as both a model to the parent and child for embedding functional communication into everyday opportunities.”

Thanks for reading the discussion so far. What comments do you have to keep the conversation going?

Image thanks to Enrique Meseguer from Pixabay